Implementing Domain-Driven Design and Hexagonal Architecture with Go (3)

How I structure my application according to Hexagonal Architecture aka. Ports&Adapters

This article was originally published on Medium in 2020!

Basics & Definitions

I will not try to explain all the details of Hexagonal Architecture in this article. Instead, I will focus — as the title says — on how I implement it with Go and where it diverges from how other people structure it. Partially because of the nature of Go, partially because of Domain-Driven Design, and partially caused by my taste. It took me a while to figure this out for myself and — as with many other things — there is no one right way, but many possibilities.

all models are wrong, but some are useful ;-)

From “first principle”, Hexagonal Architecture seems quite straight forward. As Thomas Pierrain pointed out

what really matters is what’s inside and what’s outside (of the Hexagon)

No surprise — the devil is in the detail. But don’t despair, there are some great resources to learn about the basics.

I’ll start with the YouTube videos where Alistair Cockburn explains it in depth — together with Thomas Pierrain — who does the live coding in this talk:

Alistair in the “Hexagone” 1/3

Alistair in the “Hexagone” 2/3

Alistair in the “Hexagone” 3/3

You probably figured out already that Thomas is very much involved in spreading the message about this paradigm, so please visit his blog and probably start with Hexagonal architecture: don’t get lost on your right-side. Make sure you don’t miss his next post Adapters are true Heralds of DDD where he describes a little shift in his mindset about the role of the Infrastructure code!

Last but not least there is a great article from Juan M. Garrido Paz that helped me a lot to understand the topic much better: Ports and Adapters Pattern.

Sadly, Juan passed away not too long ago- may he rest in peace.

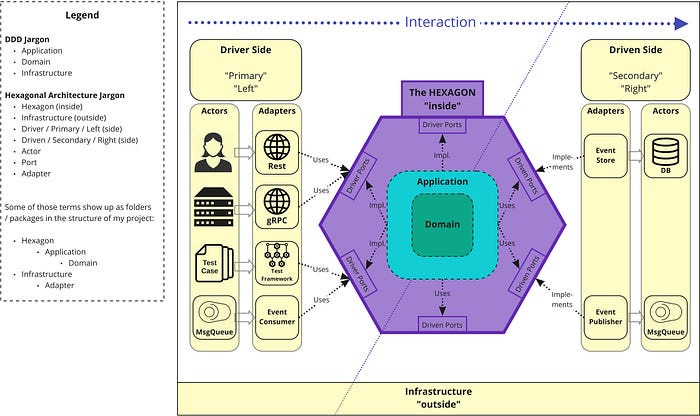

I need to define some terms and how I’m going to use them in this article.

Actually —just like Juan — I prefer Ports&Adapters as a name for the pattern, but Hexagonal Architecture is the more popular term, so I’ll mostly stick with it.

Hexagonal Architecture and Domain-Driven Design have a loose relationship. You can do the one without the other — but it seems many people use both approaches together. I have already used the terms Domain, Application, and Infrastructure quite heavily in Part 2 and it is the Domain-Driven Design based jargon I will use in Part 3!

In pure Hexagonal Architecture lingo, there is no Domain and the Application “layer” is often called the Hexagon. The term Infrastructure is used in both parlances. If I pick up Thomas Pierrain’s quote from above, the core principle of the pattern is to separate the Hexagon (Domain + Application) from Infrastructure. This separation requires to follow two basic rules:

Dependency inversion: Domain and Application define the interfaces, Infrastructure implements them.

Don’t pollute Domain and Application with infrastructural concerns.

Hint: The Application layer in the Domain-Driven Design sense is (also) an intermediary between Domain and Infrastructure and sometimes it’s very hard to keep it completely free of infrastructural concerns, for example when it comes to database transaction handling. If the price is too high to abstract this away it might be a good decision to allow some pollution!

As much as I can tell many folks coming from Domain-Driven Design focus on this core principle and ignore some details and nuances from Hexagonal Architecture. This is 100% ok — software development should not be dogmatic!

The “hex diagram”

There seems to be an unwritten law claiming that each article about Hexagonal Architecture / Ports&Adapters must have a hexagonal diagram — so here is mine.

Hint: I have not yet implemented event publishers or event consumers — they are contained in the image to give a more complete picture.

Disclaimer: I ruthlessly stole some ideas for this diagram from Juan’s post which I linked above!

The Structure

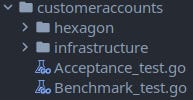

We will start with the top-level structure of the bounded context Customer Accounts and unfold it as we go.

This reflects the core principle I described above — the Hexagon and Infrastructure are top-level folders inside the bounded context.

Here’s a piece where I deviate from “pure” Hexagonal Architecture style — those two tests files Acceptance_test.go and Benchmark_test.go. According to Ports&Adapters they are Driver Adapters and should live under Infrastructure, probably in a test package.

In Go, it is idiomatic to put tests next to the production code they test. This works fine for classical unit tests. My acceptance tests as well as the benchmarks don’t mock any Infrastructure — some would call them “integration tests” — so they test the Hexagon and the Infrastructure and I put them to the closest possible spot. This also “feels” right for me. Otherwise, I would have to go a long way down and up the tree from the Hexagon to locate those tests. So this decision is based on idiomatic Go (a bit) and personal taste, nothing more, nothing less. By principle, they are still Driver Adapters!

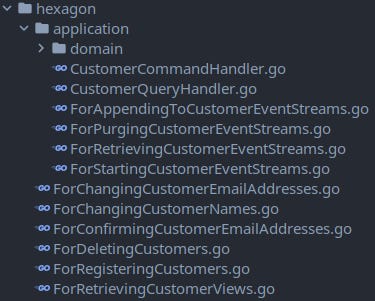

The Hexagon

We find Driver Port interfaces in the lower half — named according to ForDoingSomething — as well as application which in turn contains Driven Port interfaces following the same naming scheme. This interface naming is a bit special and as far as I can tell many people are following a different naming scheme like IDoSomething, which is well known from classical interface names in Java and other OOP languages.

You might have noticed that all those interfaces are fine-grained, they map to single methods. Actually, they are not even interfaces but Go’s function types. I have mentioned those in Part 2 already.

My fine-grained ports / function type interfaces, e.g. ForRegisteringCustomers (Driver Port) or ForAppendingToCustomerEventStreams (Driven Port)

are not everybody’s taste.

The alternative (coarse-grained) could look like this: ForHandlingCustomerCommands andForStoringCustomerEvents

I don’t like the technical name of the Driver Port interface and generally, I prefer small interfaces. The Driven Ports already have quite technical names, so it makes more sense there. On the other hand, mixing fine-grained and coarse-grained feels a bit inconsistent. For coarse-grained interfaces, I’d have to use real interfaces instead of Go’s function types. The latter additionally have a technical role. I can use functions as test doubles instead of using a mocking framework or a hand-crafted mock object. Last but not least I’m using those functions similar to higher-order functions. I say similar because I use constructor injection into the objects that depend on them instead of passing them in method calls.

Long story short: I like the explicitness of fine-grained interfaces.

Heuristics to make such a decision could be:

amount of interface methods per Port?

are Commands defined in Domain or Application?

does the CommandHandler act as a Command Bus with a

Handle()method or does it offer explicit methods for each Command like in my implementation?

Application wraps Domain

As far as I can tell, many people who implement software that follows Domain-Driven Design and Hexagonal Architecture paradigms have 3 top-level folders (packages, namespaces, …)

Application (or App, …)

Domain (or Model, …)

Infrastructure (or Infra, …)

So it seems relatively straight forward why both Application and Infrastructure are top-level folders. I decided to put my Domain layer into the Application layer so that Application is like a shell around Domain (it wraps it).

I have made some jokes about my limited ability to make decisions in P1 and P2 of this series, so let’s continue: I have changed this about 5 times already, moving Domain in and out of Application. This is quite stable for a couple of weeks now so I guess I’ll stick with it. ;-)

Thinking in terms of use-cases this structure gives me excellent functional cohesion. Any request hits the Application layer first, either a CustomerCommandHandler or the CustomerQueryHandler. Those Application services will then use Driven Ports which are implemented in Infrastructure to do the persistence stuff (read and write) and finally dispatch to the Domain layer to handle commands, build views …

There is almost a 1:1 relationship between the capabilities of the Application layer and the Domain layer. The only exception is Driver Port interfaces defined in Domain (e.g. ForBuildingUniqueEmailAddressAssertions described in Part 2).

The flow is always uni-directional from Application to Domain. This is different between Application and Infrastructure where quite some ping pong is going on.

This is purely my taste and putting domain next to application and infrastructure instead is 100% fine!

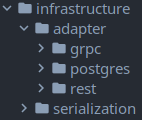

The Infrastructure

I don’t want to dive into the details here — I’ll write another part of this series about Infrastructure implementation. For now, I just want to explain what is shown in the picture.

Oh my, this “another” part never happend, I wrote about other things instead …

I have a top-level folder adapter which probably only exists because there is a package serialization on the same level. Additionally, I like to give a little of the Ports&Adapters flavor here. As we can see with serialization there might be other infrastructural concerns that are not tied to adapters. For the time being, I could also move serialization into the postgres folder. Currently, I only have serialization for Events to map to and from persistence.

I have structured my adapter packages by technology here, so we have logical cohesion in this corner. I avoid that very much in other parts, but here it makes sense for me. The CustomerEventStore inside of postgres implements multiple Driven Port interfaces, so I can’t structure by Driven Ports here. This is a consequence of my fine-grained interfaces. If I’d have a more coarse-grained interface like ForStoringEventStreams I’d very probably have a package named like that (lowercase). The same goes for the grpc package, it uses multiple fine-grained Driver Ports inside of application. Finally, rest is just an autogenerated proxy to grpc so the same reasons apply here.

After a fruitful discussion on Twitter, I decided to not separate my adapters into driver/driven, or primary/secondary, or left/right, or any other convention. Given the small size of my whole sample application, it’s just not necessary. Also, the naming is a bit tricky. The terms above don’t have a meaning for developers who are not into Hexagonal Architecture. In the end, this is mostly personal taste and there are many possibilities. In a bigger application there might even be extra layers, e.g. adapter/driver/ui, adapter/driver/messaging, adapter/driven/persistence. I think it should be named and structured so that it makes sense for the team and considers the number of adapters and files needed to implement them.

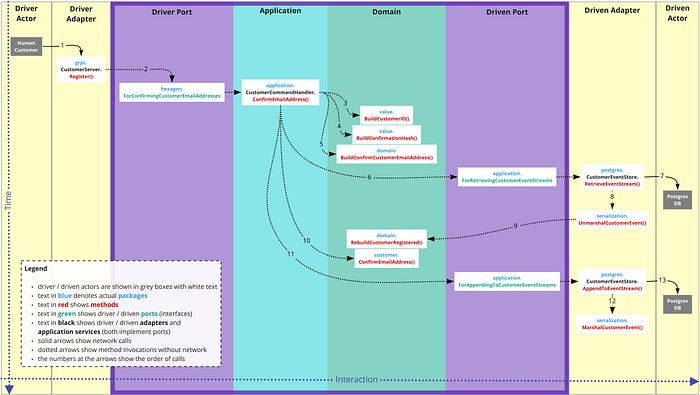

Finally: The flow through the application

A picture says more than a thousand words, so please have a look at the flow of one use-case through the layers. Please note that the colors match “the hex diagram” above (more or less).

The runnable source code is available on GitHub

Hint: This links to a branch that is “frozen” so it matches what I wrote in the blog article(s). Beware that the code, same as the original article, is from 2020 - nevertheless it should run fine.

The other parts of this series are here:

Part 1 - Introduction to the domain, the bounded context, and the business usecases

Part 2 - How I implement tactical DDD patterns — the Domain layer

Thank you for your time and attention! :-)

My articles / subscriptions here are for free, but you can support my work by buying me a coffee.